He Thought He Was Getting Football Physicals. He Was Being Abused.

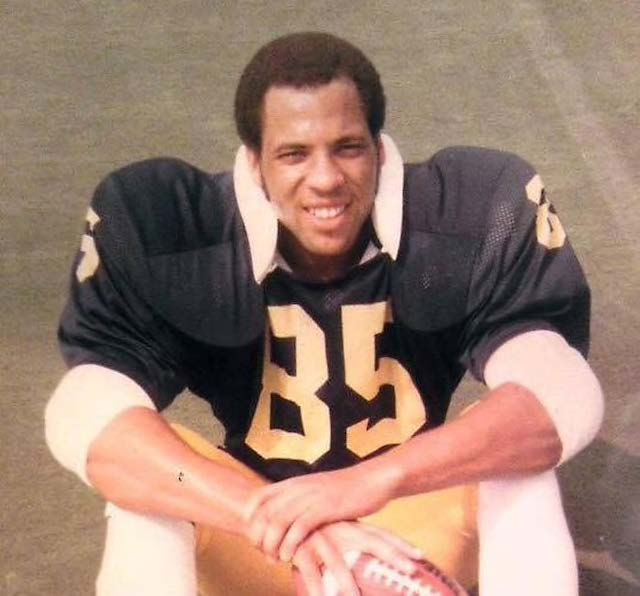

Chuck Christian played on some of Michigan’s best teams. More than 40 years later, he sees a connection between a university doctor’s assaults and a dire prognosis.

For more than 40 years, Chuck Christian did not call himself a victim because he did not think he was one.

He was a muralist who had played tight end at Michigan. He grew up poor in Detroit but came to be a world traveler. He contracted prostate cancer and outlived his doctors’ predictions.

Then, in February, an old teammate called.

Remember Dr. Robert E. Anderson? The team doctor at Michigan who performed painful, unexplained rectal exams? Someone reported him, the former teammate said, and it turns out that what he did to you, and to so many other players, was probably a crime.

“I realized that he had victimized so many of us,” Christian said in a recent interview.

Since February, when the university first revealed findings of a secret, long-running investigation, hundreds of people have complained about Anderson’s conduct. As the inquiry unfolded, lawyers said it was increasingly clear that while Michigan achieved decades of success with many of the nation’s finest athletes, it also harbored a vast sexual abuse scandal.

“I realized that he had victimized so many of us,” Christian said in a recent interview.

Since February, when the university first revealed findings of a secret, long-running investigation, hundreds of people have complained about Anderson’s conduct. As the inquiry unfolded, lawyers said it was increasingly clear that while Michigan achieved decades of success with many of the nation’s finest athletes, it also harbored a vast sexual abuse scandal.

“Dr. Anderson left a stain behind,” Christian, 60, said last month. “Now others will have to clean up his mess.”

‘It hurt like crazy.’

Christian was the youngest of four boys, and his first field was Frederick Street, on a Detroit block near Mt. Elliott Cemetery.

“If it snowed, we’d go out, shovel the snow, put on our gloves and still play,” Christian said. He was probably four or five inches too short to earn a basketball scholarship, and when it came time to consider a pile of football offers, his mother wanted him to stay close to home.

“Dr. Anderson left a stain behind,” Christian, 60, said last month. “Now others will have to clean up his mess.”

‘It hurt like crazy.’

Christian was the youngest of four boys, and his first field was Frederick Street, on a Detroit block near Mt. Elliott Cemetery.

“If it snowed, we’d go out, shovel the snow, put on our gloves and still play,” Christian said. He was probably four or five inches too short to earn a basketball scholarship, and when it came time to consider a pile of football offers, his mother wanted him to stay close to home.

“Dr. Anderson left a stain behind,” Christian, 60, said last month. “Now others will have to clean up his mess.”

‘It hurt like crazy.’

Christian was the youngest of four boys, and his first field was Frederick Street, on a Detroit block near Mt. Elliott Cemetery.

“If it snowed, we’d go out, shovel the snow, put on our gloves and still play,” Christian said. He was probably four or five inches too short to earn a basketball scholarship, and when it came time to consider a pile of football offers, his mother wanted him to stay close to home.

So each year, he braced for his physical. Each year, he said nothing.

“I knew if I said, ‘No, no, don’t do that,’ it could cause him to fail me with my physical,” Christian said. “And I didn’t want to fail my physical, because I really wanted to play football at Michigan.”

Wearing No. 85, he played in Michigan’s first Rose Bowl victory since 1965.

‘This is not supposed to be happening.’

Christian remembers being the only art major who also wore a football letter jacket at Michigan, but he followed a fairly ordinary path as he finished college. He earned his degree, married his girlfriend and moved to Massachusetts to escape a wretched economy in Michigan. He worked at a bank for a while but felt trapped and out of place.

He turned to a career in art and had three sons as the family settled into one of Boston’s southern suburbs. He would see Anderson on television during games but did not dwell on their encounters because, he said, “you tuck it away somewhere you don’t have to deal with it, don’t have to think about it, don’t have to talk about it.”

All the while, Christian generally avoided doctors and resisted the most intimate medical procedures. When he went to a doctor at age 45, the snap of a glove sent his mind scrambling to Anderson’s office, and he refused a prostate exam. About seven years later, in 2012, Christian declined to see a urologist after a worrisome lab result.

But in 2016, he began waking nearly a dozen times a night to use the bathroom.

His wife and his primary care doctor, whose discussions with Christian over the years had been mostly about his blood pressure, insisted that he see a urologist and have a complete evaluation.

The specialist checked Christian’s prostate and found it hard and enlarged. Testing revealed that it was overwhelmed with cancer cells and that the disease had spread. A blood test showed Christian’s prostate-specific antigen level was more than 16 times higher than normal, and his Gleason score, a 10-point measure of prostate cancer’s aggressiveness, was a 9.

Christian had maybe three years to live, doctors told him just before his 57th birthday.

“We just sat there and looked at each other,” his wife, LaDonna Christian, recalled. “We were just starting our lives, our kids just left, we just paid off the loans. This is not supposed to be happening.”

Anderson, who retired in 2003, was already dead.

A letter in 2018 started a damning inquiry.

Not long after Chuck Christian’s graduation, a defensive tackle from Louisiana named Warde Manuel enrolled at Michigan. More than three decades later, Manuel was his alma mater’s athletic director, and in July 2018 he received a letter from a former wrestler.

Anderson, the wrestler wrote, had in the early and mid-1970s “felt my penis, and testicles, and inserted his finger into my rectum too many times for it to be considered diagnostic.” The wrestler described a reaction much like Christian’s, a perspective that experts consider common among abuse victims: “He was the doctor, and it never occurred to me that he was enjoying what I was not.”

The letter eventually prompted a police investigation, and more people described troubling encounters with Anderson. One, who was 65 when he spoke to the authorities, said he had received more prostate exams as a student than as an adult.

According to law enforcement documents obtained through a public records request, a former vice president of student life told investigators in November 2018 that he would “bet there are over 100 people” who could accuse Anderson of wrongdoing. The former vice president said he moved to fire Anderson decades ago after learning of what was happening in the exam rooms, but instead allowed the doctor to resign to speed the process.

The investigator told the man that Anderson had never actually left the university, and the official was “visibly shaken,” according to a detective’s report.

Michigan did not disclose its inquiry until this February. (The university said its announcement had been prompted by the end of a review by prosecutors, not by a forthcoming article in The Detroit News. The prosecutors said they could not file any charges because of Anderson’s death and Michigan’s statute of limitations.)

One of Christian’s former teammates soon called him about the revelations. Christian understood at last that the exams had been criminal, not merely uncomfortable. They were also, he realized, why he had such a powerful, nearly uncontrollable aversion to doctors.

“If they had dealt with Anderson back then, he never would have violated me and all of my friends and all of the players that came after,” Christian said.

He often wonders whether more regular visits with doctors would have uncovered his cancer before it metastasized.

Although doctors who were not involved in Christian’s care said it is impossible to know when he developed the disease, Christian sobbed as he recently discussed his avoidance of crucial testing that might have detected the cancer sooner.

“I regret it so much,” he said. “I wish I had done it. But I didn’t.”

A spokesman for Michigan, Rick Fitzgerald, said in an email that the university had “great admiration for Chuck Christian and other former U-M athletes who are bravely stepping forward to share their stories.”

Lawyers have told some accusers, including Christian, not to speak to university officials or their hired investigators from WilmerHale, a law firm. Still, Fitzgerald said WilmerHale was reviewing more than 300 “unique complaints.”

Michael L. Wright, a lawyer for Christian, said he was working with about 140 former Michigan students who had accused Anderson of misconduct. Some former students who hired other lawyers have already pursued litigation against Michigan, which said in a court filing this month that it was “confronting through credible allegations the sad reality that some of its students suffered sexual abuse at the hands of one of its former employees.”

Although Wright’s clients have not gone to court, in part because of the continuing inquiry, he said he would begin litigation if negotiations with Michigan deteriorated. Wright said he expected the university’s investigation to show “an institutional cover-up.”

Christian knows it is virtually certain that he not will see the outcome of the investigations and the lawsuits that could last for years. He elected to speak out, he said, to urge athletes who may have been abused, at Michigan or elsewhere, to report what had happened.

And he has tried to come to terms with what happened to him.

“I didn’t forgive him for him,” he said of Anderson. “I forgave him for me so I wouldn’t have that poison on me, so I would be free to be Chuck, to be that loving guy who everybody knows.

“I’m not going to allow him to kill me.”